High school “Cats” lead Kentucky to inspirational Solar Car Challenge run

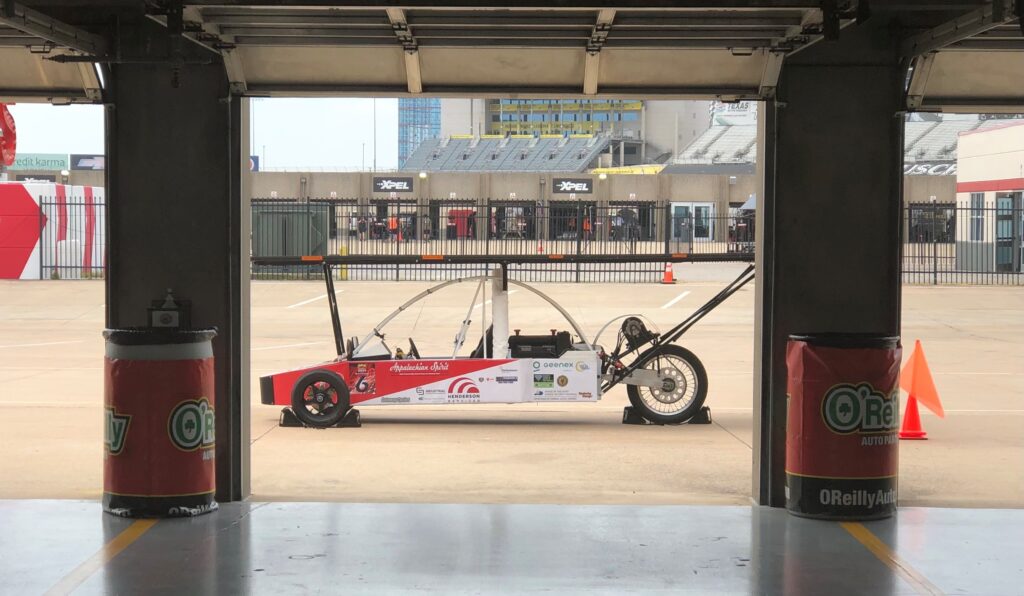

The Bath County High School in Owingsville, KY proved that there truly is something wily about cats. The Solar Cats recently became the first high school team in all of Kentucky to design, build and race a car in the Solar Car Challenge. If that wasn’t enough of an achievement, the Cats showed their prowess by placing second in the Classic Division of the 2021 Texas Motor Speedway challenge.

But the story behind the success of the Solar Cats is what makes the Bath County High School project so unique. At the core of what became a schoolwide engagement were two of the school’s teachers—Brian Coleman and Ricky Prater—who motivated the students and created a passionate spirit that propelled the solar car team to an impressive finish in the race. Soon, the community was also energized and rallied in support of the team. Other schools throughout the state have taken notice and are now starting their own solar teams.

Setting the bar high for his students is nothing new to Coleman whose background is in the IT industry and served as the Information Technology Instructor and BCHS Solar Car Racing Team Program Coordinator. “I’m a go big or go home kind of person,” he said, adding that when he joined the teaching staff at Bath County High School in 2018, he was looking for “something big” for his students that would incorporate 21st century technical skills and the soft skills that business and industry is looking for from potential employees.

Then, online, he came across the Solar Car Challenge. The Challenge was created in 1993 to motivate students to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) subjects and careers, and also to increase overall awareness of alternative forms of energy. “I asked the administration if I could start a solar car team at the school and they said, sure. But really, no one ever thought we would get this off the ground,” he added. “I just didn’t think it would ever happen either,” Prater said. “Mr. Coleman roped me into the project because I had the woodworking lab. The rest is history.”

The Solar Car Challenge is one of the nation’s largest STEM initiatives. Its purpose is to introduce students to multiple facets of engineering and design and to teach troubleshooting and problem solving, said Prater, formerly the Engineering and Technology Instructor and Technology Student Association Advisor at the school.

But building a car was only one phase of the entire challenge, Coleman said. “The students also had to complete engineering journals and they had to work on engineering schematics and wiring diagrams. They also prepared formal presentations as though they were doing them for industry, and they had to learn different types of presentation techniques: informal, semiformal, and all the way up to corporate style. They also had to learn and understand project management. They had to work on graphics, and they focused on team building and teamwork concepts. Plus, they were responsible for all the financing and fundraising and public relations.”

Solar Car Challenge projects are student-led, Coleman said, teachers are nothing more than facilitators and advisers. “We do what’s called just-in-time instruction, which means that teachers say: here’s what you need to do to get over this little hump. When students say, ‘OK, we’ve gotten to a stopping point, we don’t know where to go next,’ we switch to inquiry-based instruction, and we teach them how to do it. After that, the entire process is theirs. They must troubleshoot every aspect of the design. There are no kits. We simply give them stacks of metal or whatever materials and the students do everything from scratch.”

Coleman said that a pivotal part of the pre-race preparation and design was the students’ use of Solid Edge® to create a 3D model of the car’s electrical system. “Most people will do a traditional electrical diagram. What one of our students did was overlay the electrical system on the solid CAD drawing. The 3D models of the car showed every single wire where it’s routed on the car itself. The wiring harness itself and all the electronic pieces as well. This went over very well with the judges. The student who did this is not a 3D modeling wizard. He’s just an average student, but Solid Edge is laid out in a very intuitive manner.”

One of the things that Solid Edge provides, Prater added, is online tutorials. “This is how I learned how to use the program, and I tell my students, go online and learn Solid Edge,” he said. “I learned CAD using Onshape, a cloud-based program, but it doesn’t have the bones, if you will, it doesn’t have the bite that Solid Edge has.”

“The fact that in Solid Edge you can select your different components and bring them into the simulations, verify you’re doing a wiring harness for that, and make sure that everything is functioning properly before you actually build, is tremendous—especially when you have limited funding, and you don’t want to waste materials going in that. That’s one of the best things I’ve seen so far when comparing multiple 3D modeling software,” said Coleman. “It’s an outstanding product.”

Once the car is built and transported to the Solar Car Challenge location, the student teams go through three days of “scrutineering,” where they must defend their design and build of the car and their understanding of engineering. If a problem is found by the judges, they have time to fix it during those three days. At the end of the third day, the judges once again scrutinize the vehicles. If the judges don’t give the team a green flag to race, the team goes home.

“It’s pretty intense,” Coleman said. “The teachers have no control and cannot help them during that phase.” If student teams get the green light after this phase they enter the race, which runs over four consecutive days. Each car entering the race starts with a fully charged battery pack which is recharged through solar power brought in during each day of racing, and by energy savings associated with regenerative breaking (capturing kinetic energy during deceleration and storing it in the battery so it can be used as electricity to power the electric motor). Part of the racing challenge is to manage power consumption over the race no matter what the weather conditions may be.

“The students stepped up,” Coleman said of the Bath County High School Solar Cats. “The community got behind it something tremendous. We had sponsors come in literally from all over the state and some from outside the state.” Thanks to the Solar Cats, other schools throughout the state have taken notice of the value of the Solar Car Challenge initiative and are beginning their journey to develop a program at their school.

“It was something no one will ever forget, and the learning was amazing,” Prater added. But he retired from teaching in August, and Coleman moved to Somerset High School in Somerset, Ky., this school year.

Coleman was recruited by Somerset to enhance the school’s engineering department and start a solar car team of their own. He has become recognized as an inspiration to the students and to other teachers. He now teaches Engineering I and II courses, as well as mechanical engineering, robotics, and electrical/electronics engineering classes using Solid Edge as the primary 3D modeling software. Plus, he teaches a 3D modeling, dual-credit, course at Somerset Community College.

“At my new school, every one of my engineering classes are learning Solid Edge,” Coleman said. “I literally have it loaded up in my lab, so every single student is going to be learning this here.”

Watch out, Solar Car Challenge, Somerset is coming on strong!

For more information on Solid Edge for educators and students visit siemens.com/solid-edge-educator, and be sure to check out Siemens Engineering Design curriculum.

This article was originally authored by Think Lab Alley on behalf of Siemens.