The road to resilience at the point of design: Intelligence

In our fourth episode of the Printed Circuit Podcast, we talk about how to create resilience at the point of design through a three-phased approach, with the second phase being intelligence. This phase further applies the insights from component sourcing knowledge and couples it with part intelligence to empower more informed actions and workflows across the enterprise, lowering both cost and risk. This allows the enterprise to adapt quickly to supply disruptions.

Introduction to how intelligence enables resilience at the point of design

Resilience is the capacity to recover quickly. Basically, how you weather the storm. Today, we’re seeing new types of storms in the PCB industry unlike we’ve ever seen before, but our responses have been similarly flawed. So, diving deeper into the analogy of the storm, when you go to the supermarket to pick up toilet paper, they only have so much for a certain amount of time and then when a weather event occurs, the shelves are bare. This is very similar to what’s happening in the PCB industry. Our 20-year focus on hyper-efficiency has really led to hypersensitivity. Even smaller supply interruptions of “popcorn” parts can be a challenge.

When you talk about intelligence enabling resilience, it’s really the application of “outside-in” intelligence from across the electronics value chain that allows you to understand and reliably predict the weather. The earlier you can predict the weather, the earlier you can utilize that intelligence to make the right design decisions. So, it’s outside-in intelligence, it’s the ability to not only search for parts based on parametric information in your corporate library, but it’s the ability to access extended intelligence during those searches that include a leading indicator like “popularity”, for example. These represent parts that are the most popular based on patterns of new industry-wide design cycles. Or intelligence from searches that take into account diversity of alternatives, demand at time of design, and supply risk. So, if there’s a weather event, you won’t run out of toilet paper water or other necessities. Matter of fact, you’ll already be prepared because a risk alert would have lit up your smart phone before the actual event is even on radar.

How supply chain business challenges have evolved over time

The biggest problem back in the day may have been RoHS– meaning that you were just trying to make sure that your components met a specific requirement. It was also cost. Lead time was not the biggest challenge because you typically had enough leeway to do your design work, then send the initial Bill of Material over to component engineering to check for obsolescence and AVL compliance, and then onto the sourcing team to have them procure. Those days are over. Now, lead time, availability, and even counterfeiting are becoming huge issues.

When we first started designing PCBs, even sharing information was different because we barely had computers that were attached to a network and, therefore, sending data electronically was not as important as it is today. We must share electronic information a little bit differently, not just exporting out some format and then sending it over the wall, you need to have a cohesive and collaborative environment. We need to have more and more connected solutions because we have more and more connected devices that require more and more electronics. So, for example, my refrigerator now can tell me if I’m out of food.

Redesign is expensive. When a component engineer, or worse, a procurement professional, tells you, “I can’t get that part,” and you already spent weeks, if not months, designing and simulating the board, it becomes extremely expensive to rework.

The evolution of PCB design

Board designers and circuit engineers traditionally have had three competing perspectives they need to address simultaneously to be successful designing boards:

- Layout solvability. You’re solving to place and route your parts and connections in any circuit, whether it’s a standard or HDI, and mastering your CAD tool while you’re doing this.

- Then you have your signal integrity and performance.

- The third perspective is design for manufacturability. Is your board designed for producibility? It’s easy to make one of something. Much harder to make hundreds of the same thing.

In the end, the goal is to take these three perspectives into consideration, and you’re going to have to make decisions where it’s a give and take to accomplish all three. In the end, your goal is to make revision one work. It’s tough if you are doing this, but you don’t have the insight to the component details from the supply chain. This is what we have been missing all along – part intelligence at the point of the design.

Real examples of supply chain issues

A customer we met with about six months ago explained to us that their supply chain problem wasn’t just ICs anymore, but now included “popcorn” parts: resistors, diodes, and capacitors. And this represented new challenges. One of the real-world examples that they shared was that they designed-in an IC that worked at a specific frequency. Unfortunately, that specific IC was not available anytime soon. Typically, you might search for something that meets that threshold but never exceeds, but in this example, they actually were able to qualify the same IC at a higher frequency speed grade and were able to procure that one more easily. So, design-for-lowest-cost isn’t the top consideration anymore, it’s what do we need to do to get revision one working that can ramp to volume on time? It’s balancing availability, costs, and design feasibility.

Another couple of examples are in the automotive industry. If you’ve gone out to try to buy a new vehicle, it can be very difficult right now. Behind the scenes some automotive companies are removing touchscreens from models. And other manufacturers are eliminating all their HD radios and their heated seats because they couldn’t get the right chips required for them to do the development.

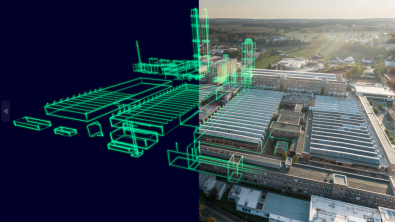

Adapting to the new normal with expanded scope of intelligence

We are engineering in a new normal. To adapt, you now need push-button access to expanded intelligence, availability, pricing, comprehensive searchable parametric information, and models—a component digital thread that unites cross-functional organizations. We talk about digital threads within Siemens all the time. In EDA, we focus on the design digital threads that include ECAD-MCAD and verification, for example. but the component digital thread touches all of them and is an extremely important element. The component digital thread does not just include searchable electrical information or physical package parametrics that we extract and consume from content providers, but it’s also rich supply chain data that goes beyond what’s stored on enterprise systems.

As you’re selecting parts during the design process, you need to have that expanded intelligence at your fingertips. If a particular part doesn’t meet your cost vs. risk envelope, you need that same single source of supply chain intelligence to determine if there are alternates. You will also want to continually audit your design BOM and do a health check to see if you’re still meeting your price, availability, and risk rank. You may also want to be able to compare different parts — again, not just electrically but also at the supply chain intelligence level. So, as I mentioned earlier in the Mil-Aero example, a particular part might be available at a higher frequency, and another at a higher cost, but in terms of availability, it’s readily available. With that intelligence you can balance those trade-offs.

Another key piece of the intelligence is the active risk alerts. There may be time when something happens in the middle of the night and some impact of a geopolitical event or environmental issue is felt. Back to the weather analogy, you want an alert that says there’s a storm brewing and you need to prepare.

Today, there are plenty of tools out there that can take a Bill of Material and run an audit. But there are no out-of-the-box solutions that can connect all the stakeholders of the NPI process, for example, together with the same single source of supply chain intelligence. And this is what’s going to allow our customers to weather that storm and create the resilience to face any of the growing challenges of this normal or the next normal.

Work is currently underway at Siemens to enable this intelligence phase. In our next episode, we’ll dive deeper into the third phase of creating a resilient supply chain, which is optimization.

Want to learn more about the intelligence phase on the road to supply chain resilience? Listen to the podcast now, available on your favorite podcast platform.

Expand to see the Transcript

[00:12] Steph Chavez: Hi, everyone. Thanks for tuning in to the Printed Circuit podcast, where we discuss trends, challenges, and opportunities across the printed circuit engineering industry. I’m your host, Steph Chavez. As a refresher, I’m a Senior Product Marketing Manager with Siemens with over three decades of experience, and I’m an industry knowledge subject matter expert in PCB design. I am also Chairman of the Printed Circuit Engineering Association (PCEA). Joining me today is Andre Mosley, Marketing Development Specialist with Siemens. Andre, thanks for being here. Can you give a quick introduction?

[00:44] Andre Mosley: Yes, Steph, thanks for having me, I’d be happy to. I’ve worked for Mentor Graphics—now Siemens EDA—for about 25 years. I started off as a consultant, focusing on component and library technologies. Then I transitioned my roles into both customer and product marketing. And now my role is Market Development. And that is to say, I’m focusing in on electronic integrations and data management concepts that help our customers align their business needs to our robust Siemens portfolio.

[01:15] Steph Chavez: So, on our last episode of the Printed Circuit podcast, we talked about the road to resilience and how we can enable that transformation in three phases, which is knowledge, intelligence, and optimization — the first being knowledge. Today, let’s dig into phase two, which is intelligence. When I think of intelligence, we look at this with respect to it’s about further component insights that enable actions to solve for both cost and risk. This allows the enterprise to adapt quickly to any supply chain disruptions. Andre, how do you think intelligence enables resilience at the point of design?

[01:50] Andre Mosley: That’s a good question. I think the first thing is to tackle what does it mean by resilience, and that’s really the capacity to recover quickly. In the PCB world, I call that PCB Process Toughness. And my analogy to that is how you weather the storm. And living here in Florida, of course, I’ve learned how to do that. And realistically, we’re seeing new storms in the PCB industry unlike we’ve ever seen before. Typically, when you talk about supply chain, over the history of supply chain, we’ve tried to be hyper-efficient. So, the analogy of the storm, when I go to the supermarket to go pick up toilet paper, they only have so much for a certain amount of time. But when a weather event occurs, they run out of inventory. And it’s very similar to what’s happening in the PCB industry, where this hyper-efficiency has really led to hypersensitivity. So, the smallest interruption can be a challenge. So, when you talk about intelligence enabling resilience, it’s really part intelligence, being able to understand and predict the weather — I need to know what’s going to happen. So the earlier I can predict the weather, I can get that part intelligence to my engineers so that they can make the right design decisions. So, it’s part intelligence, it’s the ability to not only search in the databases that I’m used to seeing today, but it’s doing extended searching that provides me some additional component information that allows me to maybe take my design and do things like a Bill of Material analysis, or even compare against different parts. So, if there’s a weather event, and I know that I’m going to be out of toilet paper, is there another option on the table? The ability to do a comparison of those different parts, and also do some sort of risk alerts. So, again, I want to get that weather alert like we do on our cell phones when there’s going to be a problem, I need to translate that into the PCB industry so that I can get that intelligence. And then, again, maintain that resiliency and be able to recover quickly. And if you don’t have this upfront, it can be extremely expensive to recover. So, Steph, I know you’ve worked in the Mile-Aero industry, and I’m sure you can confirm that it takes a long time to recover when you don’t have this information.

[03:58] Steph Chavez: You’re absolutely right. I will tell you, in my last 13 years or 12 years before I transitioned over to Siemens, especially in the last two years, one of the last projects I worked on before I left the supply chain pain is what I refer to is it just hit us hard. When you think about how many times within the process of designing during the design cycle, we had to stop, take a step backward, and then go forward. But it was like two steps back or one step forward. And that iterative process just took so much time, and time is money. You talk about schedule time and then the additional costs of unexpected hours of redoing steps over and over. It was just brutal, not just for me, but for the entire team. And like I said, I refer to it as the supply chain pain. It takes time. When you submit a part request, at an enterprise level, it could take up to three to five business days to get a part released in the system. The component engineer is the first person that looks at it, he or she decides whether it’s available or not available, does it meet all the requirements, and the specs that are necessary to get released into the system. If it doesn’t, it gets rejected, and the EE has got to go back and research his part, and make the decision, “Do I hope to find another part? Or do I redesign it with a different circuitry? Or do I eliminate that feature entirely?” And it’s not just him making that decision, it’s the project team. And it’s a negative ripple effect that happens over and over within the process. And today, with what we’re seeing in supply chain with the disruptions, we are all feeling this pain. So, like I said, I can attest to it, it’s real and it’s there. Andre, since you started in the industry, how have you seen supply chain business challenges evolve over time?

[05:35] Andre Mosley: It’s kind of funny, both you and I have a similar history. It’s a long, valued history. So, when I started in the industry, a lot of the problems weren’t that acute. The biggest problem back in the day may have been RoHS, meaning that you were just trying to make sure that your components met a specific requirement. Maybe it was also cost. But lead time was not the biggest challenge because you had enough leeway to do your design work, then send the Bill of Material over to component engineering and have them procure and identify that. But now, like the challenges, you spoke earlier, this is really becoming a huge issue with our customers: lead time, availability, and even counterfeiting, and the need to make those changes very quickly. The world has exponentially sped up on us, so even sharing electronic information back in the day when we first started, they barely had computers. So, sending data electronically was not as important. Now, in the day of Amazon, you expect to have a result within 24 hours. So, in the PCB industry, we have to share that electronic information a little bit differently, not just exporting out some format and then sending it over the wall, you need to have a cohesive environment. So, we need to have more and more connected solutions because we have more and more connected devices that require more and more electronics. So, for example, my refrigerator now can tell me if I’m out of food, and it’s a highly competitive market. And as you suggest, redesign is expensive. So now when a component engineer tells me, “I can’t get that part,” I just spent weeks, if not months, designing this and simulating it. So, it’s not just I can’t get the part, I’ve got to reengineer this and it becomes extremely expensive. Steph, I’m sure you’ve experienced a lot of these types of challenges, specifically at mil/aero. As your role as chairman, how do you see this affecting the three perspectives of design?

[07:30] Steph Chavez: From the perspective as the Chairman of PCEA, where the whole essence of PCEA is collaborate, educate, and inspire. The fact is, as board designers and circuit engineers, there are three competing perspectives that we have to address simultaneously in order to be successful in designing boards, which is layout solvability, that’s where you’re solving to place and route your parts and connections in any circuit, whether it’s a standard or HDI, as well as at the same time, you’ve got to master your CAD tool while you’re doing this. Then you have your signal integrity or your performance, where’s your signal integrity, power delivery, your thermal, EMC stuff, it’s the performance of the board itself. The third leg or the third perspective, we are addressing is your manufacturability design for manufacturability designed for producibility, where you want to consider producing high yields at lower costs. And in the end, the goal when designers are attacking their boards is to meet these three perspectives, and you’re going to have to make decisions where it’s a give and take. And in the end, your goal is to make this revision one work. That’s the ultimate goal. And it’s tough if you are doing this, but you don’t have the insight to the component details from the supply chain. And this is where I feel what we have been missing all along is that part intelligence at the point of the design. I can tell you if we had this intelligence at the point of design, it would have saved so much money, so much time, and so much heartache. And PCB West this year, that was one of the discussions that you would hear in the hallways and in between the classes and even some of the classrooms. I discussed this in my industry best practices session. And in my discussion with Rick Hartley, Susie Webb, Mike Creedon, Thomas Chester, Dan Beaker, and Ben Jordan, it’s there. And this is stuff that’s in our face, and we’ve got to deal with. It’s definitely a challenge nowadays. I mean, board design has definitely evolved, it’s not like in years past. When we think about our experience working with customers all over the globe. Especially as we evolved into the global days now, where COVID has shown us that we can be effective with global teams, what are some of the more interesting customer examples with respect to how supply chain resilience has affected them or how they’re evolving with the supply chain? Or do you have any experience that you can share?

[09:57] Andre Mosley: Yeah, I do, actually. I’ll leave out a couple of customer names, but it really goes to the give-and-take you talked about earlier, where you have to make revision one work. Given the lack of insight, what are our customers doing? So, there’s an example I have of a miller, a customer we met with about six months ago, where they were explaining to us their supply chain problem where wasn’t just ICs anymore, but it was actually becoming popcorn parts: resistors, diodes, and capacitors. And this represented new challenges. They are a mil/aero company, which means they’ve been in the industry for decades, understanding the impact of not being able to procure parts. But nowadays, again, it’s becoming more and more complex, so they have to revamp their entire supply chain strategy and how they can provide this information to their designers. And one of the real-world examples that they gave me is that they had an IC that worked at a specific, let’s say, frequency. That specific IC was not available, but as they search for different alternates, typically, you’ll search for something that meets that threshold but never exceeds. But in this example, they actually went to a higher frequency IC, and they were able to procure that one more easily. So, it’s not just cost anymore, like we talked about earlier, it’s I need to get revision one working, as you said earlier. It’s balancing that give-and-take, it’s now availability, costs, and can actually build this device that I want to build? Another couple of examples are in the automotive industry, and I have been seeing this recently, I think all of us have experience, if you’ve gone out to try to buy a new vehicle, it is very, very difficult. But what we don’t also see behind the scenes are places like BMW where they’re actually removing touchscreens from several models and they’re having to work with their suppliers so that they can get these touchscreens into their line of vehicles. You can think of BMW as one of these high-end luxury vehicles, you would imagine that they would all have touchscreens, but actually they will not. Another example is Chevy or GM, they’re actually eliminating all of their HD radios and their heated seats because they couldn’t get the right chips required for them to do the development. So, again, it goes back to what you said earlier, that revision one must work and I have to do this give and take. So we’re actually removing functionality so we can meet our timelines because we can’t get the devices that we want now. Now, you mentioned earlier about PCB West. I think you went there last week. So, can you talk a little bit more about what was the word on the street out there? Did you see any customers?

[12:30] Steph Chavez: So, PCB West was the highest activity and highest attendance that has been, I’d say, in 10 years. It was crazy. The biggest thing is, I think, people are just excited to get back out in person. Don’t get me wrong, the virtual world is great, it serves this purpose. And what we have found, going forward, the silver lining in COVID is that we can be extremely effective with global teams, and we don’t have to be in the same timezone, the same state, country, or whatever. So PCB West had a gathering of industry professionals from all over. And it was amazing to see, like I said, the volume was at its highest. This is a guess, don’t quote me on this, but I’m guessing there were about 1500 to 2000-plus people that attended, which is as high as the buzz. How do we adapt in the new world with less resources, tighter budgets? And how do we evolve? And how do we evolve and adapt to what we’re seeing with the supply chain in the old methodology and the old way of thinking? We’ve got to evolve from that. You can continue to do the old way, but you will slowly fall behind and fade away. You have to adapt to the new real. And the new real is that you’ve got to have this intelligence and you’ve got to have this foresight at the point of the design. And the engineers have got to know this and got to have this information to make intelligent decisions as we see and as we unfold. In the hallways, you’d hear people discussing their issues of what they’re running up with. Even leading into PCB West, a good friend of mine, who owns his own business. I won’t mention his name, but he’s EE. And a couple of the experiences he told me was that running his own company, parts that he’s been purchasing that were like $2 are now like $20, lead times have gone from a few weeks to maybe 52 weeks. So, it is real and this is a real problem.

[14:53] Steph Chavez: These are the type of discussions why it’s important, in my opinion, to attend industry conferences because you can’t get that kind of integration and that kind of feedback from the industry of “How are you guys doing it? What are you guys doing that I can bring back these golden nuggets to my company or my team?” And let’s apply this to be successful. This is where industry collaboration allows us, respectively, to be better and more effective. But it does no good if, first of all, you don’t attend and you do nothing because then the question becomes what is the cost of doing nothing? That’s another thing you’ve got to look at. And then if you bring these golden nuggets back, but if you don’t apply them. Or what I mentioned in my best practices session was that the biggest resistance or the biggest hurdles you’re going to come up against is internal company resistance within your own culture. The culture within your company, is it open to change? Or is it resistant to that? And I can tell you, coming from Mil-Aero and several you might want to consult, I see a lot of this regarding internal culture resistance within a company. That’s definitely an issue. So, yeah, PCB West was hot. You’re going to see a lot more with not just PCB West but with a lot of other industry cultures that are happening and unfolding today. Supply chain resilience is definitely a hot topic. You see it in articles, you see it in publications, whether it’s PCD&F magazine or I-Connect007 magazines, you see it all over being discussed. So, yeah, it’s definitely an issue. When we talk about the solution or where do we go from here? We see the industry is specifically evolving to resolve these business challenges. The customers are seeing, in terms of intelligence, an optimizing resilience. Andre, what do you think, what is your take on that?

[16:37] Andre Mosley: Well, it’s kind of what you were talking about earlier. We now have what I like to call engineering in the new normal. It’s not our whole old engineering environment. We touched on some of these topics earlier, but let me go into a little bit of detail. So, first and foremost, it’s about intelligence. So, it’s not just, “Hey, the intelligence is out there.” But giving me almost push-button access to that intelligence, availability, pricing, and parametric criteria, including models. So, I refer to this as a component digital thread. We talk about digital threads within Siemens all the time. But a lot of times we focus on the design digital thread, but the component is really a subset of that and it’s an extremely important piece. So, there’s this component digital thread that is not just the electrical information that we’ve evolved into extracting and getting from content providers, but it’s also the supply chain data. So as I’m doing that design, as I’m choosing that part, I’d like to have that intelligence upfront. And if I do find a problem, I want to be able to search internally first because, typically, our local customer databases will have a set of parts that we know that we can procure. But let’s just say it doesn’t meet my criteria, once I find that part or I perform the query on the part I want to find, I look in a local database, but I need to extend that out into the industry for the details to give me that part intelligence, so I need to see what’s outside my corporate library? Are there alternates? Can I do some what-if scenarios? And when you combine that together, you can do some sort of analysis. If I have a design, I always want to continually audit this design and do that health check to see, “Hey, am I still meeting my price and my availability or is there any risk?” So, I usually use that Bill of Material to do that analysis.

[18:30] Andre Mosley: And again, if I find a problem, I want to be able to compare different parts — again, not just electrically but also at the supply chain level. So, this part maybe, as I talked about earlier in the Mil-Aero example, it might be at a higher frequency or even a higher cost. But in terms of availability, it’s readily available, so I can make those trade-offs that you talked about earlier. It’s about making sure revision one works, it’s about give and take. And lastly, its risk alerts because a lot of the times, a lot of these things will happen in the middle of the night and we won’t even know the impact of geopolitical issues or environmental issues or just a run on components. I’m not sitting there every day pushing the button to say, “Do I have a problem? Do I have a problem?” I need to have risk alerts. So, if I have a corporate library, I have a Bill of Material, I want to be able to run those alerts and communicate to me to say, “Hey, Andre, there’s a weather event coming. There’s a storm brewing and you need to prepare.” So, we’re really expanding the intelligence across these different areas, it’s electronic information, its supply chain data, and even the models that go along with that so that I can very quickly redo my analysis or my simulation. In terms of your question, where do we go from here? Customers need full solutions, not just tools. There are plenty of tools out there that can take a Bill of Material and run an audit. But there are not a lot of solutions out there really to connect all of these pieces together. And this is what’s going to allow our customers to weather that storm and create that resilience that we talked about earlier in the face of these growing challenges.

[20:03] Steph Chavez: Absolutely. Especially when you think about the manual way, the old approach, and what we need to evolve to is. It’s like you say, the digital integration in that thread that’s happening. So, with that said, we’re just about out of time so I’d like to wrap up and summarize what we were able to discuss today. Today, we talked about what is intelligence and how its the second phase on the road of resilience. We talked about the evolution of business challenges and how challenges are only increasing; they’re only getting worse. And we talked about a few customer supply chain examples. And lastly, the evolution of intelligence and how these technologies enable resilience at the point of design. So, on behalf of my colleague, Andre Mosley, I’d like to thank you all today for your time. And I hope this discussion has been helpful and insightful, and understanding how you can get to the road to supply chain resilience. Thank you, and I hope you can continue to tune in and follow me on this Printed Circuit Podcast.