The death of shopping

“How often do you go shopping?” That is a question that would result in many different answers from different people. Actually, it might be better phrased: “How often do you do shopping?” As much purchasing is done without leaving home. This has been the case for many years, with mail-order and telephone shopping being popular long before online businesses appeared. How is shopping changing? Will it be different in the future? …

Shopping, as we know it, is a relatively new idea. Fixed-location shops have only existed for a few centuries. The concept of having the shops concentrated in one place on “Main Street” [or, in the UK, we would normally refer to the “High Street”] is much more recent still. Over the last few decades this idea has been slowly eroded by the development of dedicated shopping sites – malls or “shopping centers”. I hear a lot of shop owners here talking about the “death of the High Street”, which I think is a rather plaintive cry about past events; out of town shopping has thoroughly eclipsed them already. But now it is some of the best-known chains that are going out of business and they blame online shopping.

The reality is that shopping, like many things in life, needs to evolve – to move with the times. I am not against “traditions”, but continuing to do something in a particular way, just because you have always done it that way, is simply illogical. Conventional shops will continue to have a place, but for many purposes, online shopping is better in every way – for the consumer, the economy and the environment. Different ways to run shops will emerge – I wrote about this topic here – and there are many exciting possibilities. The events of the last few weeks have changed things [that was an understatement!] and with the temporary closure of many shops, online sales have benefitted. But this is really just a disruptive influence that is progressing an existing trend.

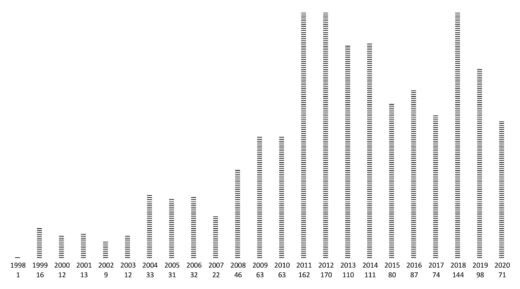

When lock-down was eased a little recently, shops selling “non-essential” goods reopened. At first, I thought that this might be useful. Then I realized that I had no particular requirements; I had not missed these shops when they were closed. I have been an enthusiastic online shopper for many years – since the late ‘90s. I thought that it might be instructive to analyze my Amazon usage. The earliest order shown on my account was in December 1998, but I am sure I used them before that. Maybe I had another account then. I can see how many orders I have placed each year:

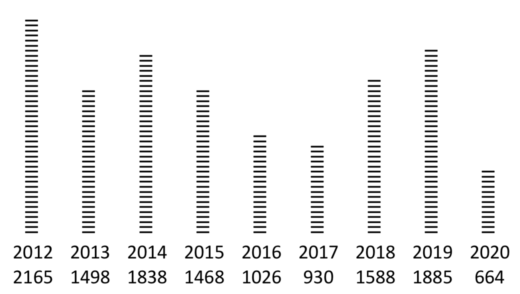

I expected a steady rise and was surprised by the bumpiness in this graph. However, this is number of orders, which will have been affected by factors beyond my desire to buy stuff. For example, Kindle purchases are often for a single, low-cost item. Also, I have subscribed to Amazon Prime for a few years and that does not encourage consolidation of orders to save on shipping costs [Amazon do that for you!]. I wondered whether the amount of money I spent with Amazon each year would be more interesting. This would be possible, but very time consuming, to extract from my Amazon account. So, I turned to my credit card, which enabled me to plot numbers for the last 8 years:

That was not too helpful either. It seems that I am not a really big shopper with them after all, even if they are often the first place that I look. The numbers are too strongly affected by the occasional larger purchase and this hides any trends. The simplest conclusion that I can glean from this data is that using Amazon has saved me, on average, one shopping trip each week over the last few years.

I have encountered many people who are keen to boycott some multi-national companies because there are arguments about the amount of tax that they pay [or, rather, do not pay]. I feel that this protest is misdirected. Most, if not all, countries have tax systems firmly rooted in the 20th Century [or earlier]. Accommodating multi-national companies, who can trade anywhere at any time, was never considered. So, it is obvious that tax collection will fail. However, the fix is quite straightforward. Broadly speaking, the focus should be on indirect taxing [Sales Tax or VAT], which could readily be tuned to be fairer. I wonder how much VAT Amazon has paid to the UK government, for example …

A type of shopping that I have felt is less amenable to online operation is food. However, particularly in recent weeks, the big supermarkets see a huge demand for delivery services. I suspect that some habits, formed during the crisis, may persist. For fresh food, there is an opportunity for smaller, more local businesses. We have had a vegetable box delivered every week for several years. This is a different experience from choosing your own items, but, for the most part is a wholly acceptable alternative. It needs a different mindset. Instead of planning meals and going out to get the veg, you need to operate the other way around. We have recently found a butcher who delivers very conveniently. The key thing with these businesses is customer confidence. They need to generate trust by offering good quality, variety and service. Price still matters, but, within reason, these other factors can offset its importance.