Reinventing the wheel. Again?

It is long enough ago now that I can look back on when I first started writing embedded software and begin to really understand – or perhaps admit – why it attracted me. It would be easy to say that I liked a technical challenge – and I did. I also liked the sort of kudos of working on something that felt very state of the art, even if explaining what I did to lay people was challenging [it still is!]. However, I have come to accept that what I really liked was the opportunity to have almost God-like power …

What I found exciting was the idea that I could take a microprocessor, with an empty memory, fill that with code and make it do something. It was almost like giving it life. I later found out that life evolves and that would be a problem. So, I need to be careful with my analogies. I will share the challenge that I brought on myself:

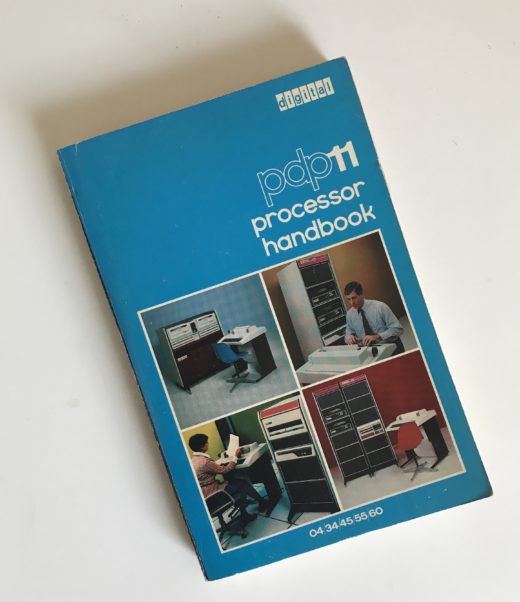

In my first job, I initially worked on real-time systems that controlled materials testing machines. These were based on mini-computers – mostly DEC PDP-11s. A challenge with these machines was the operating system. We needed to create multitasking, real-time applications, but the standard operating systems, RT-11 and RSX-11, were not really designed for this. RT-11 was very lightweight [amazingly similar to MS-DOS that would come along a bit later] and, as its name implied, could be use for real-time applications, but it was a single-task OS [actually you could run a background task as well as foreground, but that did not help much]. RSX-11 was a possibility, but was much more focused on supporting multiple users. We were fortunate enough to have a very smart guy on the team, who addressed this problem by writing a new operating system, which had a simple time-sliced scheduler that enabled the straightforward design of real-time applications. [He also wrote a FORTRAN compiler for it, but that is another story.] For me, being “on the inside” of the development of this OS was a wonderful learning experience, which I would apply in the years to come.

In my first job, I initially worked on real-time systems that controlled materials testing machines. These were based on mini-computers – mostly DEC PDP-11s. A challenge with these machines was the operating system. We needed to create multitasking, real-time applications, but the standard operating systems, RT-11 and RSX-11, were not really designed for this. RT-11 was very lightweight [amazingly similar to MS-DOS that would come along a bit later] and, as its name implied, could be use for real-time applications, but it was a single-task OS [actually you could run a background task as well as foreground, but that did not help much]. RSX-11 was a possibility, but was much more focused on supporting multiple users. We were fortunate enough to have a very smart guy on the team, who addressed this problem by writing a new operating system, which had a simple time-sliced scheduler that enabled the straightforward design of real-time applications. [He also wrote a FORTRAN compiler for it, but that is another story.] For me, being “on the inside” of the development of this OS was a wonderful learning experience, which I would apply in the years to come.

Some years later, in a different job, I was developing an embedded application and needed a multitasking kernel. I was working with an 8-bit device [Z80], not a PDP-11, but I figured that I could create a kernel based on the same concepts that I had learned years earlier. And that is what I did. It only took a couple of weeks and the kernel enabled the application to be completed with what I felt was a good, maintainable design.

For my next project, I also decided that such a kernel was needed. So, I took my previous code, made a few enhancements to it and used it for the new application, which went well. Some months later, I did the same again: enhance the kernel and use it in yet another project. At this point, I was very pleased with myself. I really felt that I was mastering the key skills of embedded software engineering. I did not know that I was about to learn a new lesson.

My next project was an upgrade to an earlier system – the one for which I wrote the original kernel. So, I got out the code for the application to refamiliarize myself with it. I was rather shocked. I could hardly recognize the kernel code at all, as my later enhancements had transformed it a long way. Although I could easily port the newer code into the old application, this was all a bit of a surprise. I realized that I had not created a kernel – I had created three! Like living things, my code had evolved and evolution, whilst effective, is very messy.

In due course, I left that job and moved on with my career. The code I left behind was in a reasonable state and fairly well documented. However, if, instead of reinventing the wheel, I had obtained an existing kernel and used that, I would have left something more maintainable. Of course, I did not know that commercial kernels were even available. And it would have been much less fun! I often advise developers, even today, that creating their own OS is unwise, but I do understand why they might be tempted.

In a way, I am sad that things have changed. An engineer today, developing an embedded application from scratch is almost inevitably reinventing the wheel – pointlessly recreating something that has been done perfectly well before. They are denied that feeling that something was “all my own work”. Having said that, there is much to be said for getting back to basics and reimagining designs. Perhaps there is a different and better way to make a wheel …