The Leanest Lean You Have Ever Seen

Lean manufacturing represents a cultural change at all levels of a company. Its prime objective is to eliminate waste, whatever form that takes. The most obvious examples in the production area might be excess materials in storage, work-in process, and finished product waiting for buyers, but it can also be unnecessary movement of staff and many other processes that do not ‘add value’ to finished items. The objective is to deliver orders on-time with minimum inventory with the shortest lead time and highest possible utilization of resources adding value.

Most lean initiatives start with a process called Business Process Re-engineering. This really is a formal way of analyzing how we produce things and identifying tasks or areas where no value-add takes place. The process then moves onto what is termed ‘lean thinking’. This is about looking at average production rates for each product (Takt Time), load leveling (Heijunka) and process redesign to attack the waste problem.

Process redesign will often use techniques such as Kanban to provide an easily understandable and visual method of controlling the movement of materials and controlled by demand order pull rather than what has been called MRP push. This type of production control is sometimes referred to as a Visual Production System or VPC.

Many consultants see VPC as central to lean initiatives but, in reality, it is just one step along the road to the ultimate lean environment which is Make (or Build) to Order or MTO. Why is this? The ultimate test of how lean you are is to ask the question – if you stopped accepting orders today and then waited until the factory stopped how much inventory would you have left? If it is none then you are truly in a MTO environment but if you relied on Kanban systems, only final assembly or dispatch are MTO. All upstream processes are Make to Stock. Kanbans are simply a better and more visual way of controlling inventory. It’s not the leanest of lean and, while demand is fairly stable they work very well, but they are less able to deal with variable demand.

To understand why we have reached this situation we must understand the past. Before MRP, Materials Requirements Planning, we had EBQ or Economic Batch Quantity. This used a minimum batch size in order to try and increase the value-add time (changeover time between batches being non-value-add) or purchase in quantities that provided lower costs per item from our suppliers (they liked big batches too!). MRP software was introduced to provide a way of synchronizing the manufacture and purchase of parts based on lead times for each based on aggregated dependent demand but still used EBQ that created inventory. VPC reduces this inventory so that the EBQ is one Kanban full. Even if a Kanban is one part, we are still in effect making to stock.

So how can we get better? APS represents the ultimate step to lean manufacturing. If you have MRP then get the system to make to order and turn off the make to stock features (if you can). This will generate a batch for each order you have and at each level of the Bill of Materials. The APS software can perform the dynamic aggregation of batches to minimize changeover times by sequencing these smaller batches in a way that they become the ‘big batch’ we want at critical process steps where resource throughput is a key element of productivity and efficiency. Often there is a trade-off between minimizing changeover time and delivery performance and a ‘what if’ tool to see the impact of dynamic aggregation is essential to making the right decisions.

The following APS rule implemented in a food processing company illustrates this well. It has been simplified to a single process line but in essence the company wanted to maximize resource utilization (which to them meant minimizing changeover time) but ensure all delivery dates were met.

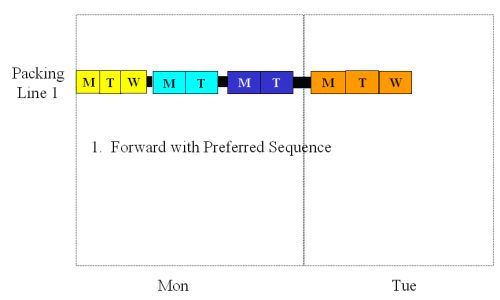

The first ‘pass’ of the rule scheduled the orders onto the process line in a preferred sequence. In the illustration Packing Line 1 has had number of batches sequenced yellow – light blue – dark blue – orange. The letter on each batch is the Due Date, M being Monday, T for Tuesday and W for Wednesday.

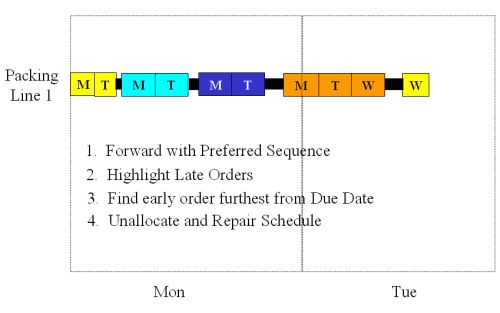

In this case we have an orange order which will be completed on Tuesday which has a Due date on Monday. The rule identifies this situation and looks for a batch which has the greatest time between completion and due date. In this case the third yellow batch due for delivery on Wednesday is found.

The next pass of the rule removes the yellow Wednesday Order, shuffles up the others (referred to here as schedule repair) and puts the yellow order on the end of the schedule.

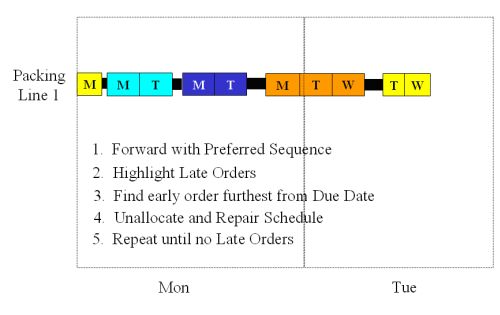

In this case process is repeated because we still have orange Monday order late so the yellow Tuesday order is reallocated in the sequence.

The sequence that minimizes changeovers while making all due dates has now been obtained.

Here then is a good example of how APS software has helped to sequence batches to minimize non-value add time, in this case changeover time, while making sure we deliver all the product on time to our customers.

In summary then, APS and Lean initiatives are complementary. Business Process Reengineering is used to identify issues to tackle, VPC in the form of Kanbans reduce inventory but do not eliminate it. APS provides a decision support tool to the planner to help eliminate non-value-added activities and get deliveries on time.

This brings into focus another issue. Kanbans or other forms of Visual Production Control delegates scheduling decisions to the shop floor whereas APS empowers the planner to make the scheduling decisions which are then passed onto the shop floor to execute. Is this a good idea?

If you use VPC, scheduling decisions are based on empty Kanbans. The emptying of a Kanban triggers the filling of it by operators. However, they are working in isolation. They have no other visibility of other processes, not late arriving orders, nor do they have knowledge of key performance indicators (KPIs) such as minimizing late deliveries, minimizing production costs and so on. Variations in demand will cause problems that the operator can not be aware of.

If an APS tool is used scheduling decisions such as changes in priorities for customers are based on company wide KPIs and the planner has the whole picture with which to make the tradeoffs that are bound to be required. Variations in demand are handled more easily and the shop floor has a single KPI – schedule adherence.

A good example of where complete elimination of work in progress and finished stock is in the food processing industry where freshness of raw materials and shelf life of finished product is a real concern. They are in the forefront of planner empowerment and many other sectors can learn from their experience. They have:

-

- Short shelf life products

-

- Short shelf life materials (including packaging)

-

- Can have delivery lead times less than the manufacturing lead time

-

- Have a highly variable demand (due to weather and promotional activities)

-

- Are affected by severe hygiene requirements

-

- Have alternative recipes

-

- Have very demanding customers (particularly the large multiples where shorting is a big issue)

-

- Have flexible but variable labor

In this industry VPC is almost unknown. The status of the planner is very high and in many companies APS has become a key decision support tool in making the company responsive, efficient and profitable. In these companies a single KPI, schedule adherence is all that is required at shop floor level and supervisors can focus on meeting this rather than dealing with a thousand and one other issues.

About the Author

Dave Snyder is a MOM Channel Sales Executive at Siemens Digital Industries Software. Dave has 30 years’ experience in the Advanced Scheduling space.