Why failure IS an option: Frontloading @ Realize Live

My favorite quote, from my favorite movie, comes from Ron Howard’s 1993 docu-drama “Apollo 13”, as Gene Kranz (wonderfully played by the actor Ed Harris) addresses a crowd of NASA engineers and flight controllers and implores them to find a way of bringing the crew of the recently crippled spacecraft safely home:

“We’re gonna have to figure it out. I want people in our simulators working re-entry scenarios. I want you guys to find every engineer who designed, every switch, every circuit, every transistor and every light bulb that’s up there. Then I want you to talk to the guy in the assembly line who had actually built the thing. I want this mark all the way back to Earth with time to spare. We never lost an American in space. We’re sure as hell not gonna lose one on my watch! Failure is not an option!“

Gene Kranz – NASA Flight Director

Gene Kranz is one of my heroes and the Apollo 13 story is one of the greatest stories of engineering triumphing over adversity. I once had the pleasure of meeting Kranz at a conference and hearing him speak*. In real life, he is every bit as inspiring as his movie caricature.

However, as an engineer, and as a middle-aged man, I respectfully disagree with him on the whole “failure is not an option” thing, because in my life, and my career, repeated failure is a necessary condition for eventual success.

Put simply, if failure is not an option, then neither is success.

Repeated controlled failure

Failure is the very fabric of innovation, it’s what success is made of. At its heart engineering is a process of continual improvement. Engineers take existing things and try to make them better, usually by making a series of incremental changes that are intended to make a product somehow “better”: faster; stronger; lighter; more efficient; less expensive. Every successful product is the result of many design iterations, each of which gradually improves the performance of the product in some manner.

The problem is that for every successfully implemented design improvement, there are many more “failed iterations” that either delivered no improvement in product performance or somehow made it worse. For every hard-won improvement in product performance, there is an almost infinite number of ways to break it.

Predicting which changes will improve a product, and which will diminish it, is the art of engineering; we have to identify poorly performing design choices so that we can eliminate them. Often the lessons that are learned from early failures influence the whole future design direction of the project.

In the good old days of engineering, this process of improvement through repeated failure was almost entirely dependent on the (sometimes destructive) testing of physical prototypes in a process that was often described as “design, build, test, repeat”. Because those prototypes were expensive and only available late in the design process, opportunities for failure (and therefore innovation) were severy limited.

Frontloading: fail early, fail often

This year at the Simcenter @ Realize Live conferences we’ll be exploring the concept of “frontloaded simulation” as one of our key themes. Frontloading is the process of pushing simulation earlier and earlier into the design cycle.

During the design stage, engineering teams need a fast, easy-to-use, and accurate tool to help them understand the behaviors of the various design alternatives and possibilities early. Frontloading simply becomes a method by which trends are examined and less desirable design ideas are dismissed when the cost of change is lower. During the design phase, speed is of the essence. Engineers need to simulate not only early but also often to keep in step with the speed of design changes. By iterating rapidly, engineers can discount less attractive ideas and innovate more. Once a design has been explored and identified as viable, it can continue on to the verification stage.

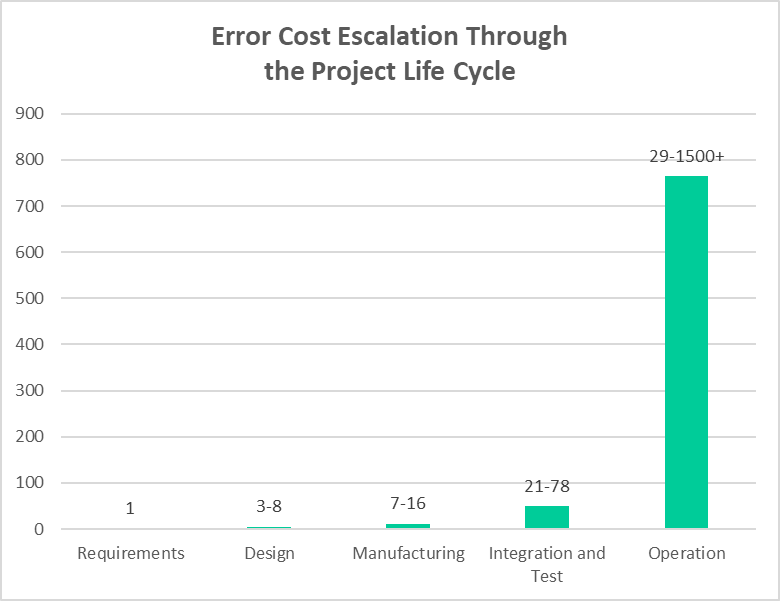

If we acknowledge that failure is essential to success, it becomes imperative to make the majority of those mistakes as early as possible in the design process because the cost of failure rises exponentially with time, as demonstrated by this 2004 NASA study:

Frontloading simulation allows you to try out innovative new ideas early in the design process when the cost of failure is low. It allows you to fail early, to fail often, and to learn from your mistakes. Ultimately this is the cost of a better and more robust final product.

We need to talk about failure more

Of course, I’m being unfair to Gene Kranz. He understands more than anyone that success is dependent on learning from your failures. Kranz’s first mission as NASA Flight Director was the ill-fated Mecury-Redstone1 launch that rose a total of four inches in the air before exploding in midair. He credits the disaster that tragically claimed the lives of three American astronauts as the most significant event of the Apollo program:

“It was perhaps the defining moment in our race to get to the moon,” Kranz wrote of the fire aboard Apollo 1. The ultimate success of Apollo was made possible by the sacrifices of Grissom, White, and Chaffee. The accident profoundly affected everyone in the program”

So rather than “failure is not an option” my mantra for the Frontloading Generation would be this:

Consumers imagine that beautifully designed products are conceived fully formed from the mind of a brilliant designer, without recognising that all products evolve through multiple failures.

As engineers we rightly take lots of pride in our successes, but I think that we all need to spend more time recognising the amount of “grunt work” that goes into designing beautifully engineered products.

Rather than adopting the macho “Failure is not an option” approach, I think that the engineers need to be more honest about their failures, and adopt the following mantra:

“Fail early. Fail often. Learn from your mistakes and share them with others.”

Stephen Ferguson

I hope that some of the presenters at the free-to-attend Simcenter @ Realize Live conference would illuminate us with their honesty.