Simulation for a fitter world

Who wants to live forever? If we’re honest, most of us would answer “no” (after all, forever is a very long time). But no one wants to die young or to spend the twilight years of their lives immobile or infirm.

The good news is that you probably don’t need to.

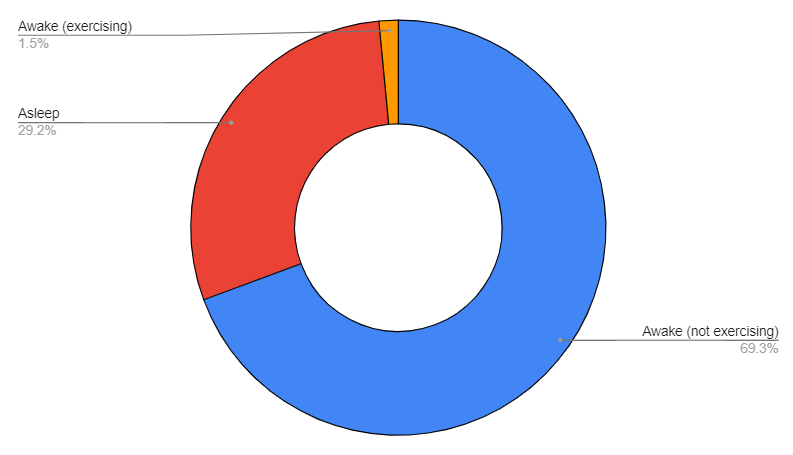

There are 10,080 minutes in a week. By spending just 150 of them participating in vigorous exercise, you can extend your life expectancy by between 0.4 and 6.9 years.

Given that on average Americans spend 180 minutes a day watching TV (or streaming services), 150 minutes a week represents an excellent return on investment. By getting off the couch and spending just 1.5% of your time exercising you can generate many extra minutes of living at the end of your life (many of which will be spent comfortably sitting on a sofa, boring companions with tales of athletic achievement).

Regular exercise will also ensure better mobility in those twilight years, contributing to both freedom and increased productivity. This is important because many of us will end up working until much later in life than our ancestors (most of whom died younger).

Sport and technology have always been linked. The advancement of athletic performance is often driven by technological (and sometimes pharmaceutical) advancement as much as blood, sweat, and tears. In this blog, we’ll explore how simulation not only enables elite athletic performance but also inspires legions of regular people to participate in fitness pursuits.

“Ladies and gentlemen, here is the result of Event Number 9, the One Mile: First, number 41, R.G. Bannister, Amateur Athletic Association, and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, Oxford, with a time which is a new meeting and track record, and which, subject to ratification, will be a new English native, British national, British All-Comers, European, British Empire and World record. The time was three . . .<a roar from the crowd drowns out the rest of the announcement>”

Announcer at the Iffley Road atheltics track on May 6, 1954 as Roger Bannister becomes the first human to run a sub-four-minute mile.

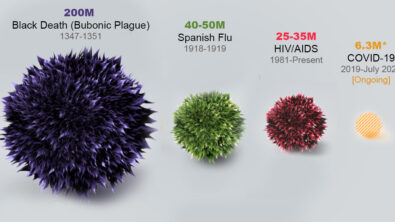

Perhaps the most iconic achievement in all sports occurred 70 years ago when Sir Roger Bannister became the first person to run a sub-4-minute mile. Although this was obviously a supreme act of athletic achievement, it’s likely that Bannister would have run slower if it were not for the then “state-of-the-art” synthetic track. Or if he hadn’t benefitted from black-kangaroo-leather track spikes. Or from the aerodynamic benefit from drafting behind his pacers (more on that later). At the limits of human performance, every marginal improvement makes a difference.

After the 4-minute mile, perhaps the next greatest barrier in athletics is the 2-hour marathon. This requires an athlete to maintain a pace of 4 minutes and 34 seconds per mile for 26 miles and 385 yards. Which is almost exactly a minute a mile faster than the pace used to set the 2 hours 25 marathon world record in 1952.

70 years on and Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge set a “legal” world record for the marathon running at an average pace of 4 minutes 37 per mile for 26.2 miles, for a time of 2 hours 1 minute and 9 seconds.

Obviously, there are lots of factors that contribute to this, not least that Kipchoge is undoubtedly the greatest distance runner of all time. However, technology played a part.

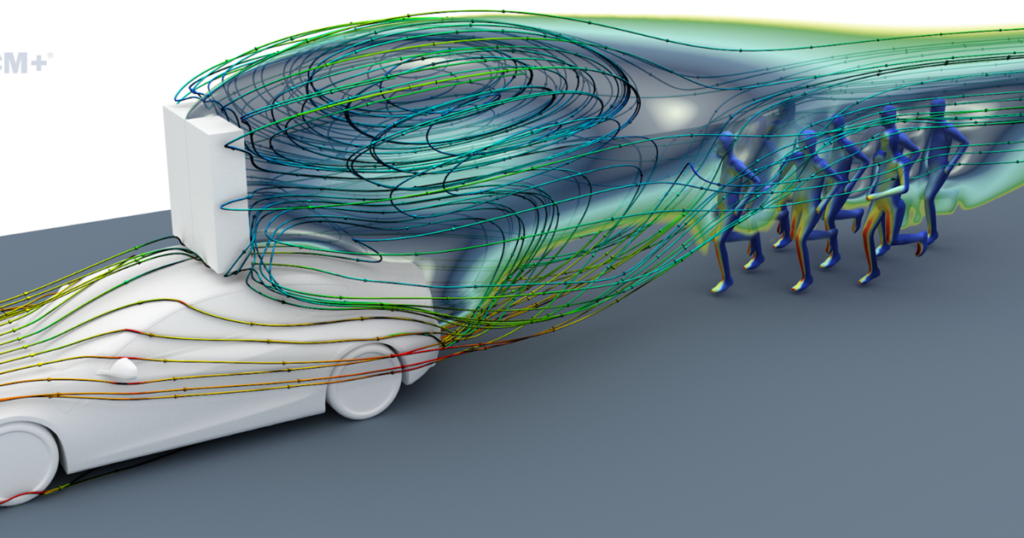

We know this because Kipchoge has run faster than this twice in “non-legal” experiments (Nike-sponsored marketing events) that explicitly demonstrate the influence of technology. In 2017, at the Breaking2 race in Monza, Italy, Kipchoge ran 2:00:25 using special “spring loaded” Nike shoes and benefits from the aerodynamic drafting behind a pack of runners and a pace car with an abnormally large clock on top.

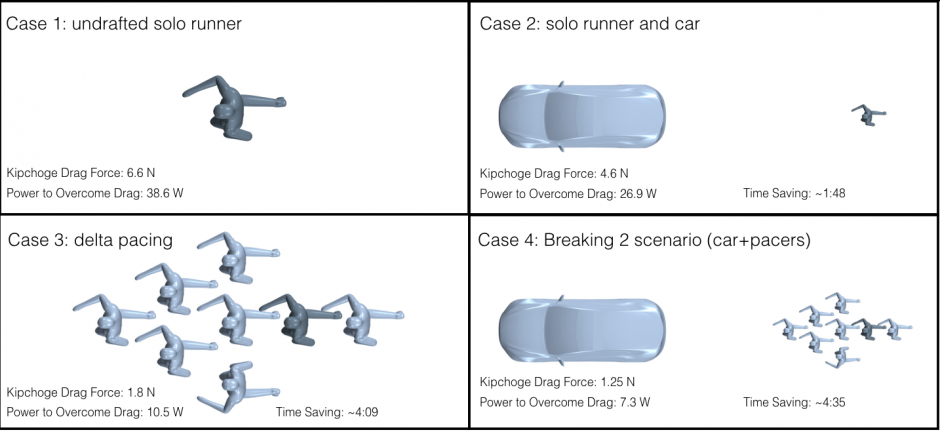

Using Simcenter computational fluid dynamics simulations we estimated that drafting behind other runners reduced Kipchoge’s aerodynamic drag by about two-thirds and allowed him to run about four minutes faster than a solo undrafted runner.

Using similar drafting tactics (and even more springy shoes) Kipchoge became the first athlete to run a marathon in less than two hours in 2019, although this is not recognized as a world record because of the technology (and tactics) used.

If drafting behind a pack of runners saved Kipchoge nine seconds per mile, it should be apparent that the faster-moving Bannister must have saved more than 0.6 seconds from drafting during his 3 minutes 59.4 world record run in 1952.

What does elite performance have to do with improving the fitness of everyday people like me and you?

Well, firstly it inspires regular people to exercise. Whether it be following Eliud Kipchoge’s example and running a (slightly slower) marathon (I’ve run six). Or pretending you are Tiger Woods while slicing a shot off the fairway.

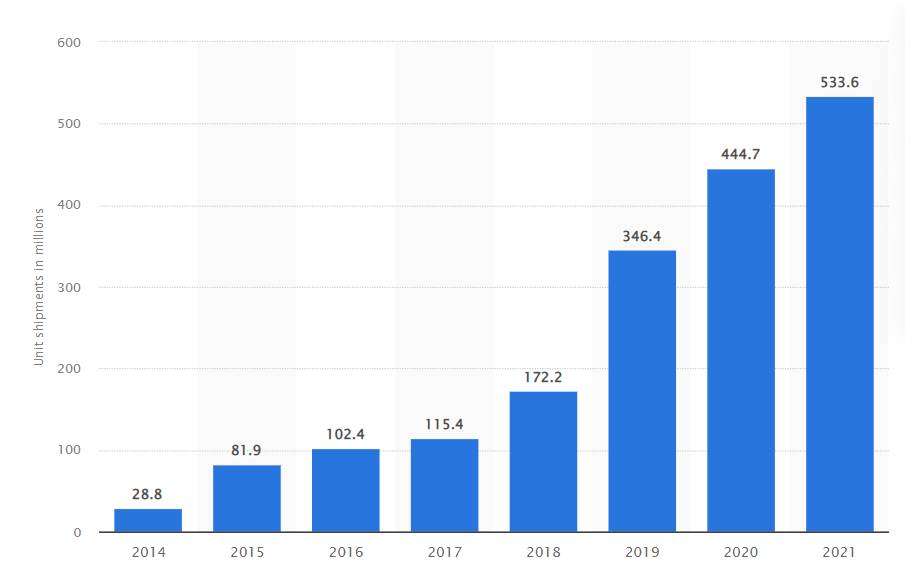

Also, lots of the technology pioneered by elite athletes is a marketing ploy to sell the same technology to regular people like you and me. Nike sold tens of thousands of the $250 shoe that Kipchoge wore to break the marathon world record. Independent analysis suggests runners wearing the Kipchoge shoe ran 4 to 5% faster than someone wearing average shoes.

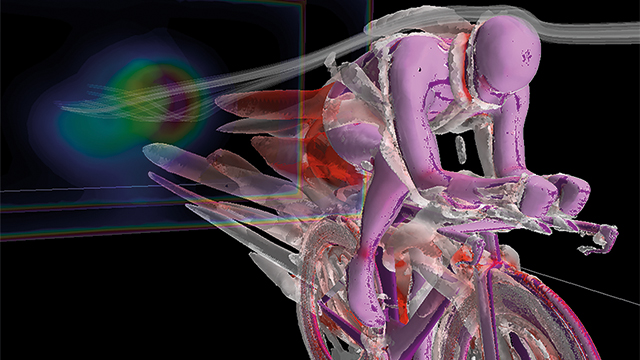

The same is true of bicycles which are lighter and more aerodynamic as a consequence of engineering simulation.

Or digitally designed surfboards (tested on digital waves) that save you from wiping out on massive waves:

Or soccer balls that let you curl your free kicks like Christino Ronaldo (although not necessarily towards the goal).

Or throw a spiral like Tom Brady (only perhaps not quite as far):

Of course, sporting and fitness activities come with the risk of injury. I have a permanently broken clavicle as a result of a cycling accident a decade ago. Simulation and tests are being used to minimize the chances of sporting injuries.

With contact sports, there is increasing awareness of the later consequences of head traumas and concussions. Simcenter has been used to understand the mechanics of rugby tackling and in particular the kinematics of the heads of players:

And similarly to model the kinematics of a soccer player heading a football, which also carries a risk of concussion:

And for those sports in which the heads of players (cycling, American Football, cricket) are protected by helmets, Siemens has an entire laboratory dedicated to impact testing on helmets:

I started this blog by saying that you can significantly extend your life by spending about 1.5% of it engaged in vigorous exercise. Having spent most of it extolling the virtues of technology on sporting performance, and how that technology trickles down into the fitness activities of regular people like you and me, I don’t want you to come to the conclusion that technology is a precursor for fitness.

Fortunately “vigorous exercise” is rather loosely defined, and includes a brisk walk, for which you need nothing more than a comfortable pair of shoes (and perhaps a warm jacket).

150 minutes a week is just over 21 minutes a day. Given that you’ve just wasted 5 of them reading this blog, now might be a good time to get out and do some life-extending exercise.