New drones for business signal the future of flight

Drones, or unmanned flying vehicles, have been around longer than most people think. The Kettering “Bug,” for instance, was developed during World War I. It was a bomb-carrying unpiloted biplane that flew on a preset course to its target.

Back then the military was the biggest drone user, and the technology usually limited drones to within the physical view of operators. Today, drones are more intelligent and autonomous thanks to sensors and systems for navigation and communications. Commercial and private uses are rapidly emerging. People call them both drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

Whatever you choose to call them, drones will have a big impact on the future of flight.

Most of us are familiar with small, recreational drones used for photography, video recording or just plain fun, but drones can range in size from miniscule, insect-like devices to much larger sizes, such as planes or sub-orbital satellites. They can safely access remote or dangerous areas, reduce delivery or assessment time and costs, and connect remotely with other drones to create on-demand communication networks when flying in “swarms.”

Insect-inspired drones are called into action in varied scenarios—from search and rescue to crop pollination. For example, Swiss company Flyability has developed a drone with a patented rotating protective frame that incorporates flight-controlled algorithms inspired by insects, such as flies. The result is the world’s first crash-resistant drone, capable of inspecting industrial facilities or carrying out mountain search-and-rescue operations.

California’s Zipline is using drones for lifesaving delivery of medical products, like blood and vaccines, to those in need—no matter where they live. Zipline operates the world’s only drone-delivery system at national scale and has recently developed what it claims is the world’s swiftest commercial delivery drone, with a top speed of about 80 miles per hour.

At the same time, global delivery company UPS recently started using drones in a hybrid combination with trucks: new electric delivery trucks have drone launchpads on top. Inside the truck, a driver loads a package into the drone’s cargo bin and drives to the next delivery while the drone flies from the truck’s retractable roof, makes the delivery and returns to the truck.

Drones may also hold the keys to last-mile connectivity and “clean” scientific advancement. The makers of Solar Impulse, the piloted solar-powered plane that circumnavigated the world in 2016, are working on solar drones that may be flying in the Earth’s stratosphere as early as this year. Their mission? Prove that clean energies work and assist with efforts such as sustainable agriculture, weather forecasting and ocean management.

Still, Solar Impulse is not the only company working on solar-powered drones. U.S. social-media giant Facebook has developed a solar-powered drone, Aquila, that will eventually be able to fly for three to six months at a time and beam Internet, the Facebook app and connectivity to those below it. This could open the door to new ways of providing last-mile connectivity to remote or underserved areas, or providing needed connectivity during a disaster.

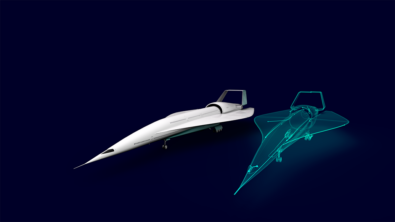

And there is more drone innovation to come. Leading global manufacturers and startups are already working on autonomous planes to transport people and cargo, and even flying cars that will create new forms of urban transportation. However, these vehicles will have to be proven safe before a new wave of alternative transportation can take off.

The future of drones is bright. As communications technology and the airworthiness of drones continues to advance, so will their use cases and benefits.

This concludes part one of our series on how flight is changing. In part two, we discuss the potential of flying cars.

About the author

John O’Connor is the director of product & market strategy in the Specialized Engineering Software (SES) organization of Siemens PLM Software. SES develops and markets CAD-integrated, specialized engineering software for product design and manufacture in the aerospace, automotive and other design-driven industries. O’Connor has served in numerous roles at Siemens, ranging from application support and technical sales management to business development. Prior to Siemens, he was a senior design engineer at Lockheed Martin, where he led a number of product design teams. He holds a Master of Science in materials engineering and a Bachelor of Science in mechanical engineering.